The other day I was running a workshop to define competitive strategies at a client company. Five minutes after the scheduled start time the first few participants wandered in. Twenty minutes later everyone was there. Were these lapses in discipline clues to their competitive problems, or simply the way it is in business today?

The fact that everyone was eventually there physically, did not mean they were mentally present. Mobile phones vibrated constantly. Blackberries were consulted obsessively. People left the room to take calls. Thumbs compulsively punched out SMS messages. Much of the communication was task-related, with people seeking input from clients and colleagues or remotely accessing data on their desktops; much of it had nothing to do with the task at hand. Yet the work got done, everyone contributed effectively, and the result was better than any had hoped for.

This apparent lack of focus is not a unique phenomenon, nor is it a recent development. But it has become more and more pervasive over the past few years. There was a time when I would ban mobile phones from meetings. Then I simply banned their ringing out loud. I realize that we are living in a radically different communication paradigm to that of a few years ago. We are now able to multitask in a way that was simply not done in the 1980s. Back then, most people did not have the skills or the tools to “parallel process” productively, and if they did, it was something done in the privacy of their own office. Politeness was our way of denying that we were unable to do many things at once without chaos, or apparent rudeness, ensuing. It’s interesting how digital deftness has corroded punctuality and redefined attentiveness, by changing our sense of time, place, and focus.

Our perceptions of what is "normal" behavior are determined by the habits of our most familiar peer groups. Over the years I have done a lot of work in various Latin American and Asian countries, South Africa, and most of Europe. In a business meeting context, the sensitivity to punctuality and attentiveness is always less cultural than contextual, and within that context you cannot make sweeping statements about national cultural attitudes or behaviors because corporate culture plays a major role in guiding those attitudes.

There are a couple of companies that I have worked with in Mexico and Brazil where -- counter to the false national stereotype of unreliability and lack of urgency -- I am always the last to arrive at my meetings, the other participants eagerly glancing at their watches as start time approaches. Conversely, there are companies in the US and UK where -- counter to the false national stereotype of task-focused discipline -- I have given up expecting more than half of the participants to be punctual, and where participants come and go at will (physically or mentally) throughout the meeting. Our concept of appropriate ground rules for interacting in a formal business meeting, no matter what its purpose, is being changed, not by e-learning, but by a growing culture of constructive disruption.

Some of us, fortunate enough to have graduated in the age of Aquarius, are most comfortable with the lava-lamp mindset, where we can endlessly watch things unfolding slowly and elegantly. We were succeeded by the MTV generation, a society of sound/video-bite junkies, who couldn't focus for more than 15 seconds on anything unless it moved dramatically, constantly. Then the post-MTV perpetually-looping CNN mode of communication produced people who assume that there is no beginning or end, believing that they can always catch up no matter where they start or how often they get distracted.

That fractured attention span seems to be getting even more fragmented with the advent of SMS and other remote communication technologies. The latest generation of company recruits thinks and behaves in genuine non-linear random-access modes. This internet generation, the “digital natives” born into a world where personal computers were already pervasive, is a society of text-bite junkies who can't think unless they are thinking about many things at once. To support this, text is making a comeback, fleshed out by a resurgence in cryptic iconography. Instant messaging, SMS, chat-room style communication, ticker-style news highlights on TV. All of it is text, but not as Shakespeare knew it. Text has a new Morse code that evolves and mutates daily. If u hve smthg 2 say, it takes 2 long to cre8 a pic. Or it did before camera phones came along. :-) LOL.

A picture is not worth a thousand words to communicators who can instantly infer complex meanings from cryptic alphanumeric string-sets. A picture is too limiting, too defined, too unambiguous, too unchallenging -- and way too unspontaneous.

Is internet culture overwhelming organisational culture? The digital divide (if we think of it in terms of those who have embraced connectedness versus those who just get by) is just getting wider. True, "smart mobs" can coalesce and disperse with split second precision. But these are funky folks on the fringe, not mainstream people in the workplace. What may become more pervasive, particularly as mobile phones become smarter and Wi-Fi becomes ubiquitous, is a blurring of the line that separates "presence" from "absence". Perhaps technology will be used to inflict punctuality and attentiveness. Or, more likely, technology and parallel-processing mental modes will make these concepts unnecessary, outmoded, and counter-productive.

Tuesday 13 February 2007

Constructive Disruption in a Wired World

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

14:16

0

comments

![]()

Corporate Spin and the Mythology of Management

What on earth are we teaching people in “management training” courses? The more senior managers I encounter, the less impressed I am with either our training practices or our promotion processes, or both. In organizational management, there seems to be a growing sense of self-righteous despotism, cosmetically made over as leadership, in an ecology characterized by denial.

There has always been a lot of lip-service paid to “employee nurturing” in organizations. Our Vision, Mission, and (especially) Values statements bask in a PR-conscious preciousness that rarely reflects the reality on the ground. Upholding human dignity, respect for the individual, fairness, equal opportunity, striving for excellence, all drip from the earnest clichéd prose used by corporations to describe their management regimes. But, in most companies, at the one-on-one, manager-to-employee level, it’s a sham.

There’s a disconnect between the myth and the reality of corporate life. Proving the effectiveness of marketing, many employees actually believe their employers’ propaganda, even though the contradictions whack them upside the head every day. Managers spout the company line back at the rare employee who plucks up the nerve to question whether in fact the emperor is naked, and with luck the confused employee starts to believe again, if only for a while. If your lifestyle (and your mortgage) has you strapped to your company, and you spend 8 to 16 hours a day immersed in the business, you have to believe simply to suppress your inner despair. The alternative is existentialism, the “it’s only a job” mentality that those too jaded to care often opt for. Beyond that, go postal, or get out. There is material here for a PhD dissertation on corporate spin and employee perceptions of reality. But you’d never find a sponsor.

Over the decades I have worked with corporations large and small around the world, and my universal impression has been that most people manage by fear and manipulation, and they get ahead by polished bureaucracy, skilful (or instinctive) use of politics, networking above themselves, avoiding risk, and exploiting their peers. The warm, fuzzy, touchy-feely stuff so beloved of HR policy wonks and management training gurus is a whitewash that obscures the reality: at the individual level, people-management in corporations is all about taking credit and passing blame.

If this is a result of incompetence or indifference, then perhaps training is at fault. But often it is a result of calculated competitiveness in those with ambition for “bigger things,” or desperate attempts at maintaining control in those already out of their depth. As consultants, we prefer to ignore these realities, because formally acknowledging them is career suicide in companies that are in denial.

In upper-middle management you have a cadre of political officers who discourage any challenge from below to the illusion of impeccable decency and high standards in management practices. If an employee speaks out, they have an “attitude problem” and if they can’t be rehabilitated, they are often disciplined, exiled, or terminated.

Far too often, dominance rules over competence. That appears to be the natural order of things anyway, so maybe it is the best way to run a business. It’s how the military has been run for centuries, and 20th Century business organization was derived from military organization, with command-and-control hierarchies the central pillar of most corporate designs. Sadly, the military has always done a much better job of managing talent.

The dog-eat-dog environments in which most employees operate tend to allow those with bigger teeth and less restraint to advance ahead of those who may be better qualified but less ferocious, or less sly. Nothing is more guaranteed to have you occupying the same desk for decades than doing a good job and passively waiting to be recognized. The result is a top-tier of management whose unifying characteristics are ambition, ruthlessness, and a sense of infallibility, and whose integrity, decency, and fitness for task may be questionable.

It is that mix of characteristics which gets companies into trouble. It is how mega-corporations lose billions in only a few months. It’s what leads to the commonplace firings of thousands of workers, a gesture that says “I have absolutely no constructive ideas how to manage my business out of the hole that I put it in, so I’ll just dump overhead.” Bizarrely, such acts of desperation are routinely applauded by analysts as indicators of strong management.

That self-serving indifference to employees also leads to another commonplace management practice – instead of simply re-organizing a department, everyone in it is instructed to re-apply for their own job. “You have been working for me for years, but I don’t really know who you are or what you do, so sell yourself to me.” In the contorted world of management-speak, this grotesque process is seen to be clever, yet it is really another admission of management failure.

Individual employees are routinely ignored, stifled, oppressed, mentally abused, and in other ways subjected to enormous stress that has nothing to do with their roles or tasks. Good people are played off against each other. Managers nurture those least likely to threaten their jobs or their egos, and sideline those whose competence makes them uncomfortable. Getting ahead these days typically requires a good performer to change companies. None of this is good for the health of an organization.

There’s something wrong with this picture, but what, if anything, is to be done?

Should we heroically be trying to train managers to act in the best interests of the company, even when it is not in the best interest of their own careers? Should we be training managers to recognize and respond appropriately to self-serving practices in those reporting to them? Should we be training employees how to get ahead, giving those who are by nature less assertive the skills and insights to compete? Or is this all futile – should we simply stick to regurgitating Argyris, Ansoff and Maslow, and hope that nobody ever notices that we are not in touch with day-to-day realities?

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

14:13

0

comments

![]()

Brief Guide to Questionnaire Design

Recently so many people have been asking me to review their questionnaires and surveys that I thought I’d update a document I first created several years ago which sets out some essential best practices for creating good questionnaires.

1. Ask: “Why are we doing this?”

- What do we need to know?

- Why do we need to know it?

- What do we hope to do when we find out?

- What are the objectives of the survey?

2. Ask: “What are we measuring?”

In training evaluation, what you measure can be influenced by the learning objectives of the course or curriculum you are measuring:

- Knowledge

- Skills

- Attitudes

- Intentions

- Behaviours

- Performance

- Perceptions of any of the above

Your questions, and possibly your survey methods, will differ accordingly.

3. Be aware of respondent limitations.

- Where possible, pilot your questionnaire with a sub-group of your target audience.

- The complexity of your questionnaire and its language should take into account the age, education, competence, culture, and language abilities of respondents.

4. Guarantee anonymity or confidentiality.

- Confidentiality lets you follow up with non-responders, and match pre- and post studies.

- Confidentiality must be guaranteed within a stated policy.

- Anonymity prevents you from doing follow-ups or pre-post studies.

5. Select a data collection method that is appropriate.

Consider the speed and timing of your study, the complexity and nature of what you are measuring, and the willingness of respondents to make time for you. Options:

- E-mail – fast, inexpensive, not anonymous, requires all respondents have e-mail.

- Telephone – time consuming, not anonymous, may require skill, has to be short.

- Face-to-face interview – slow, expensive, requires skill, best for small samples, qualitative studies.

- Web-based – fast, inexpensive (if you use services like Zoomerang), can be anonymous, best for large surveys.

6. Write a compelling cover note.

Where appropriate introduce your questionnaire with a brief but compelling cover note that clarifies:

- The purpose of study and why it is worth giving time to.

- The sponsor or authority behind it.

- Why you value the respondent’s input.

- The confidentiality or anonymity of the study.

- The deadline for completion.

- How to get clarification if necessary.

- A personal “thank you” for participating.

- The signature or e-mail signature of the survey manager (or, ideally, of the sponsor).

- If sending an e-mail, have it come from someone in authority who will be recognised, use a strong subject line that cannot easily be ignored, and time it to arrive early in the week.

7. Explain how to return responses.

If not obvious, make it clear how and by when responses must be returned.

8. Put a heading on the questionnaire.

State simply what the purpose is, what the study is about, and who is running it.

9. Keep it short.

- State how long completion should take and make sure that it does.

- Make questionnaires as brief as possible within the time and attention constraints of your respondents (personal interviews can go longer than self-completion studies).

- Avoid asking questions that deviate from your survey purpose.

- Avoid nice-to-know questions that will not lead to actionable data.

10. Use logical structure.

- Group questions by topic.

- Grouping questions by type can get boring and cause respondents to skim through.

- Number every question.

- Where possible, in web-based surveys put all questions on one screen, or allow respondents to skip ahead and back track.

11. Start with engaging questions.

Many questionnaires are abandoned after the respondent answers the first few questions.

- Try to make the first questions non-intimidating, easy, and engaging, to pull the respondent into the body of the piece.

- Try to start with an open question that calls for a very short answer, and ties in to the purpose of the questionnaire.

12. Explain what to do.

Provide simple instructions, if not obvious, on how to complete a section or how to answer questions (circle the number, put a check mark in the box, click the button etc.)

13. Use simple language.

- Avoid buzz words and acronyms.

- Use simple sentences to avoid ambiguity or confusion.

- If necessary, provide definitions and context for a question.

14. Place important questions at the beginning.

- If a question requires thought or should not be hurried, put it at the beginning. Respondents often rush through later questions.

- Leave non-critical or off-topic questions, such as demographics, to the end.

15. Select scales for responses.

- Keep response options simple.

- Use scales that provide useable granularity.

- Make response options meaningful to respondents.

- Make it obvious if open-ended responses should be brief or substantial by using an appropriate answer-box size.

16. Fine-tune questions and answer options.

- Keep response options consistent where possible - don’t use a 5-point scale in one question and a 7-point in the next unless absolutely necessary; don’t put negative options on the left in one question and on the right in another.

- Be precise and specific – avoid words that have fuzzy meanings (“rarely” or “often” or “recently”).

- Do not overlap response options (use 11-20 and 21-30, not 10-20 and 20-30).

- If you use a continuum scale with numbers for answer options, use a clear concept at the top and bottom of the scale (instead of “on a scale of 1 to 5, how good is it? : 1-2-3-4-5, use 1=very bad -2-3-4-5=very good).

- Use scales that are centred– don’t have one “bad” answer option and four shades of “good”.

- Don’t force respondents into either/or answers if a neutral position is possible

- Allow for “not applicable” or “don’t know” responses.

- Edit and proofread to make sure that answer choices flow naturally from the question.

17. Avoid leading or ambiguous questions.

- Don’t sequence your questions to lead respondents to answer in a certain way.

- Avoid questions that contain too much detail or may force respondents to answer “yes” to one part while wanting to answer “no” to another (e.g. “How confident do you feel singing and dancing?”).

- Minimise bias by piloting your questionnaire before it goes live.

18. Use open-ended questions with care.

- Open responses are difficult to consolidate, so use them sparingly.

- They often provide really useful data, so don’t avoid them completely.

- Doing a pilot or running a focus group before rolling out a survey can provide useful insight for creating more structured closed questions.

- Provide at least one open question so respondents can express what is important to them.

19. Thank the respondent.

- Thank the respondent once again. Reiterate why you value the input.

- If you intend to feed back results, emphasize when and how they can expect to get them.

- If you have offered an incentive, specify what the respondent has to do to claim or be eligible for it.

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

14:07

0

comments

![]()

Labels: guide, questionnaire design

Thinking outside the idiot box

The ongoing buzz about IPTV (Internet Protocol Television) makes me realize how rapidly some industries are evolving, and how relatively slowly some businesses and the training profession generally is responding.

In 1998 I engineered an invitation to the Royal Television Society conference, the biennial Cambridge gathering of 200 of UK television’s elite. Much of the conference was spent in presentations, planning, and self-congratulation on the recent coverage of Princess Diana’s funeral. The only two presentations that still stick with me were a history professor’s singularly unpopular assertion that TV was creating news rather than simply reporting it (much hissing from the audience), and a demonstration of WebTV by the now CEO of Microsoft, Steve Ballmer.

At the time a mere VP, Steve Ballmer was actually heckled. From the audience I heard all the superior snickers of disbelief and the whispered dismissals of the very notion that television might become interactive. The leading decision-makers in the industry were so conditioned by their past experiences of television that they could not conceive that any significant change might be possible, let alone desirable.

I had seen WebTV unveiled a couple of years earlier in New York, before Microsoft acquired it, and had been captivated by the notion that you no longer needed a computer to surf the web. In those days I was all about convergence, and would assail anyone who would listen with my predictions that TV, the web, and mobile telephony would collide and facilitate revolutions in entertainment, communication, and education. Of course this was not original thinking – lots of people were working toward achieving that convergence, and it was an uphill battle.

One of the people at the conference who I tried in vain to convert was a producer of Channel 4’s The Big Breakfast, whose resolute position was something like: “The internet is rubbish. I’d rather have my children watching TV than wasting their time online. You can’t get more educational than a television documentary.” The Big Breakfast was at least innocent, entertaining, predictable, and vaguely informative. But, to my mind, it seemed more worthy of the “rubbish” label than much of what was available online.

The singular lack of vision, with an edge of defensiveness, demonstrated among the television cognoscenti at the time was frustrating, but not unexpected. Even highly intelligent and wonderfully creative people have their limiting horizons and their comfort zones.

What is remarkable to me is not so much that attitudes and behaviors have changed, but how rapidly they changed. The technologies have advanced significantly in the past decade, but so too has our willingness to use them. Our notion of what a computer is has dissolved – it is no longer a grey box under a desk connected to the world with cables, but a palm-sized clam-shell on our hip. It has become almost second nature to take and send images and video using a mobile phone. E-commerce is rapidly going mobile – in Japan you can rent a car, or even get a Coke from a vending machine, by pushing a few buttons on your phone. Bloggers proliferate, entertainment and commerce exploit new media, and news coverage and commentary have decentralized and gone real-time. Now, with the imminent arrival of the millions of channels made available by IPTV, convergence is almost total.

But what of corporate training? Where are the revolutions in thinking, the exploitation of new possibilities, the creativity and experimentation? I still work with companies, some with seemingly limitless resources, who are slowly “putting their courses online” and trying to catch up with a paradigm that now belongs in the last century. It baffles me why we in training are so slow to evolve. Our role in training is to prepare people for the future, yet we cling tenaciously to the past.

Is it because trainers define themselves too narrowly, and think of themselves in “course” terms instead of in “performance improvement” terms? Or is it because companies don’t consider the value that training can bring to the organization is sufficient to justify the potential cost of innovation? Or is it, perhaps, that the current generation of management is still conditioned by its own past educational experiences, and is not capable of seeing that learning (or, indeed, business) does not have to be that way?

I know that we have only recently accepted the benefits of online courses and learning management systems, but perhaps we should continue to peer over the horizon instead of settling into a new zone of comfort?

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

14:04

0

comments

![]()

Labels: BBC, convegence, e-learning, IPTV, management, training

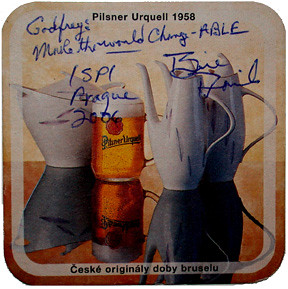

ISPI Europe Conference

Last week I was in Prague where, with my colleague Sarah Ward of ALTER Inc., I was speaking at the European Conference of ISPI (the International Society for Performance Improvement). The September edition of ISPI’s journal Performance Improvement published an article that I co-authored with Sarah and our friend and collaborator Dr. Karen Medsker on the processes required for large organisations to create a strategic approach to learning evaluation, and we were in Prague to see how those ideas fit with European business cultures.

The theme of this year’s conference was building performance into organizational culture in Europe. Presentations covered various case studies or approaches dealing with the need to increase competitiveness in the face of continued global economic pressure, and how best to improve existing job design, work processes, and organizational systems. For a small conference, there was amazing diversity in the participants – more than 40 nationalities were present. It was a little disappointing to see US speakers getting half of the air-time, though there was a concerted effort to work the lessons from existing American models into evolving European models rather than just advocate US-centric approaches. America is, after all, only America, and despite what most Americans may believe, its business culture is as unique and un-exportable as any other culture.

That said, there were many fascinating inputs from American and Canadian speakers that fuelled much discussion both in session and later over large glasses of Pilsner Urquell. Bob Evans, Director of IT Operations at France Telecom did a keynote on how he was brought in to build performance into the organizational culture of the France Telecom Group, demonstrating that often it takes someone perceived as a “crazy outsider” to shake up a calcified culture that is so habituated to its own stagnation it cannot see the advantages of change. In similar vein, Bill Daniels (author of Change-ABLE Organisation, one of the most useful books on change agentry I have ever read) talked about overcoming cultural resistance to performance improvement. His emphasis, which resonates with my ongoing focus on large-scale strategy, was on looking beyond individual performers to the system as a whole.

Other presentations covered a surprisingly broad canvas, with case studies from several eastern European countries providing a lot of practical insight into the performance challenges and solutions in developing nations.

Among the luminaries that I was delighted to get to know during the Prague meeting were Roger Kaufman, who has published an impressive 38 books on various aspects of performance improvement and is one of the most fun people I have ever spent time with at a conference; Tony Marker and Linda Huglin from Boise State, who had done some interesting work on the state of research in the performance improvement field; Mary Norris Thomas of the Fleming Group, who could be the next Celebrity Researcher; Bob Carleton who is probably the practitioners’ practitioner but shares my concern that research is moving too much toward cookery book replication and too far from rigorous case-specific craftwork; and John O’Connor of O’Connor Consulting in the UK, who spent many years earlier in his career where I grew up in Zambia (small worlds getting ever smaller). What impressed me about every conference participant that I talked with was their candour and their grounding in reality – the last thing you would expect from an organisation whose publications set very high standards and often read like doctoral theses.

Bob Carleton, Bill Daniels, and Timm Esque and his wife enjoying dinner in Prague.

I can recommend unreservedly ISPI’s European conference to anyone involved in performance improvement in their own organisations. It is a really intimate meeting where you can easily know who’s who and get to hang out and share experiences with anyone of interest – and everyone was of interest. You know you have been at a well-managed event when you look back at it and can’t quite work out how you had so many worthwhile conversations with so many people in so few days. Perhaps a key factor was that there were no vendors there, or at least none that made themselves conspicuous.

I have pretty much had it with the vast 8,000 plus conferences that I used to find so stimulating, and now prefer much smaller more focused events where you are more likely to find yourself among peers and “conferring” is more likely to happen. ISPI Europe is definitely on my calendar for next year.

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

13:53

0

comments

![]()

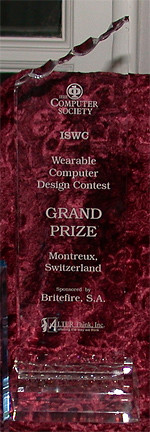

International Symposium on Wearable Computing

A couple of days ago I was a guest at IEEE’s annual International Symposium on Wearable Computing (ISWC), held this year in Montreux, Switzerland. I was there to judge entries for the annual ISWC Design Competition, and to award the check and prestigious IEEE trophy.

As the sponsor of this year’s competition, I chose to set a challenge that took the thinking away from designing ultra-expensive cyborgian machines for ultra-niche purposes and instead focused on designing ultra-cheap solutions for ultra-mass markets. I wanted to see if anyone could come up with a design for using already existing devices and infrastructures to facilitate education and training in developing countries where computers (and even electricity) are simply unavailable and where a month of web access costs typically more than the annual per capita income.

Though I did not say so in the brief, for some time I have been advocating the idea of using mobile phones (that most ubiquitous of wearable computers) and the extensive wireless phone infrastructures for core literacy and basic business education. While MIT and others are making great strides toward the $100 computer, that’s an idea whose usefulness is severely undermined by the difficulty of distributing the device and the general lack of electrical power or conventional internet access in those areas where such a machine might be most desirable. The cell phone, on the other hand, is everywhere already and it’s already connected.

Jose Gonzales explains his team's entry to Paul Lukowicz, ISWC Chair.

The winning entry was submitted by a team of graduate engineering students from Florida headed by Jose Gonzales, whose day-job is designing data-acquisition systems for aircraft in the US military. If a sign of true creative genius is the ability to dramatically reverse your perspective and still stay clear and focused, Jose is a very impressive intellect. I’d be a little concerned that I liked his design simply because it aligned rather well with my own vision, but the other judges concurred unanimously that the entry was streets ahead of the competitors. The conceptual technical design approach was well-researched, elegant, cheap, and pretty much ready to roll. Now we need the content, instructional design, a little political will, and some kind of sponsorship for both the development and the running of the phone-based learning service.

In essence, the design takes advantage of the ubiquity of GPRS (its coverage around the world is remarkably comprehensive) and its data rate of 115kbps, which is more than adequate for sending text and speech in various configurations. This is complemented by the ubiquity of devices – in places like Kebira in Kenya, more than 8 out of ten people have access to a mobile phone, though they may not have electricity or running water. Hand cranks can provide charges, or for a few cents people recharge their phones from someone running a small street-corner generator. Put your content through a free open-source Java tool that configures it so it will work and look good on any of more than 500 different phone models, and you are (at least in theory) ready to teach.

But what is the economic model? It should be possible, given the low entry cost, to get large corporations, NGOs, or even governments to front the cash for development of the content, and to subsidise the delivery. Large corporations have a vested interest in getting involved in such projects, in part because they believe in good corporate citizenship, and in part because it’s a great marketing opportunity. In fact I had a brief conversation with a Nokia representative after I had made the award announcement, and he was keen to take the discussion further. Watch this space

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

13:53

0

comments

![]()

Montreux and the ISWC Mothers of Invention

I have always liked Montreux. It is an idyllic lakeside town that would ooze class and opulence were oozing not just too tackily post-19th century. Its olde-worlde feel is overlayed with a general bearing of grace, politeness, and pleasure in service which is neither too obsequious nor too begrudging. When I lived in Switzerland in the 80’s and 90’s, I visited Montreux often en route to or from the neighbouring town of Vevy (home to the international headquarters of Nestlé and Philip Morris), and, as in the rest of the country, not a lot seems to have changed. Tipping is still considered vulgar; people still don’t walk on red at pedestrian crossings; the stores still close for lunch; and the trains still run on time.

Lounging below vine-covered hillsides at the eastern end of Lac Léman (that’s Lake Geneva to the non-Vaudoise), Montreux is the kind of resort town that Merchant Ivory would set movies in, had E. M. Forster ever written stories based there, and, of course, had Ismail Merchant not recently gone to join the choir invisible. As has Freddy Mercury, who loved the town and apparently lived out his last years there, his loyalty being rewarded by an appropriately larger-than-life statue of him jutting out his butt and punching the air in triumph as he glares across the lake at France.

Creative types have always been attracted to Montreux. Lord Byron was inspired by the nearby lakeside castle to write The Prisoner of Chillon whose opening line “Eternal spirit of the chainless mind!” could be the T-shirt slogan of the blognoscenti. Queen owns a recording studio in the town. Deep Purple burned down the casino while recording there some 35 years ago (actually, it was a fire that broke out during a concert by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention), inspiring Smoke on the Water, the guitar riff from which is also commemorated in a lakeside sculpture. David Bowie has a home in Montreux, though nobody in the town would be so indiscrete as to tell you where. Every summer a horde of jazz musicians and fans descends on the town for the amazingly wonderful Montreux Jazz Festival. Where else, as I was lucky to do one year, can you see onstage in one evening Deedee Bridgewater, Van Morrison, Georgie Fame, Santana, and John McClaughlin each playing their own sets and then jamming till the early hours with many other musical legends who are in town to listen and play?

Freddy does Montreux

This year another black-clad crowd of unconventional but somewhat geekier Mothers of Invention descended on the town to enjoy the engineering equivalent of jazz. While the inventors of the air guitar T-shirt were missing from the Montreux symposium, a few hundred other engineering students, professors, policy makers, industrialists, and techno-hucksters from all over the globe converged for a few days of future-gazing, presenting the improvisations, concepts and experiments that must surely be at one of the bloodier edges of bleeding-edge thinking.

The International Symposium on Wearable Computing melded out-of-this-world engineering, ergonomics, and human-computer interfaces with some of the more intense needs for performance improvement that exist in the real world: The GPS-linked head-up-display on fire-fighters’ visors that guides them out of smoke-filled buildings; the doctor’s hospital note taking system that works on arm gestures so as not to take attention away from the patient (pity the unfortunate patient seeing a doctor repeatedly making a sign of the cross at his bedside); the scary guy who uses his skin as a conductor to send 2 Megabits per second of data across his body, eliminating the need for iPod headphone cables; the see-through eyeglass displays and motion-sensing wrist bands that train auto-workers to install headlamps. The theory sessions, covering topics like “Humans – A Tutorial,” were even more mind-bending than the practice sessions.

For someone like me who is engaged at the application and performance impact end of technology, it was fascinating and a little humbling to spend a couple of days in the company of the brilliant minds that actually have to conceive, design, and build the revolutionary tools in the first place.

Posted by

Godfrey Parkin

at

13:52

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ISWC, jazz, literacy, mobile, Montreux, wearable computing